In a previous post, we talked about Japanese verbs and the different groups they can fall in. We also briefly touched upon how to conjugate verbs in the non-past and polite form. In trying to learn more about conjugation, I realized there’s a lot of forms / inflections and I couldn’t easily describe each of them. Because of that, I decided to write up a post talking through each of these forms at a high level. I think that understanding these forms will be helpful prior to diving deep into each one and learning how to conjugate verbs in said forms.

What are inflections / forms?

Before we go into the different inflections / forms, I want to talk about what the word “inflection” even means. An inflection is when a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, number, etc. For instance, in English, the verb “to eat” could become “I ate”, “I am eating”, “I will eat”, “I eat”, etc - depending on what we’re trying to say.

Japanese has a variety of different inflections / forms. I’m not going to go into all of them - but I do want to touch upon those that I think are the most important (based on various posts and videos I’ve read / watched). Each of these forms has an “affirmative” and a “negative” conjugation associated with it - but I’m not planning on diving into those variants in this post, either.

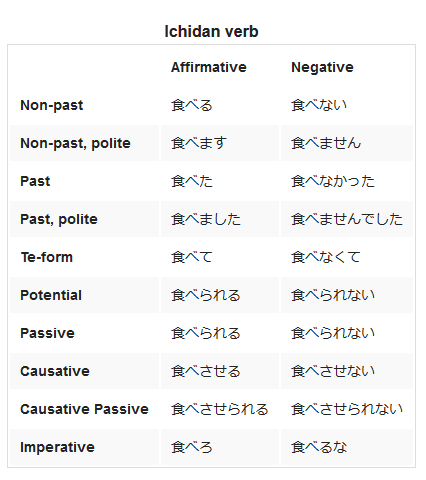

For further context, here’s a photo showing what Jisho displays when you click on “Show Inflections” for a verb:

Non-past / dictionary form / plain form

This form is the form you find in dictionaries when you look up a verb. If you use WaniKani or some other tool to study Kanji or vocab words - you’re mainly going to see this form. From this form, you can derive all the other forms once you learn how to identify which group a verb is in.

You might wonder, why is this called the “non-past” form - after all wouldn’t that imply both the

present and the future? Interestingly, that is indeed what it implies. If you see a verb in this

form, it could be talking about the present or the future. For instance, the sentence 8時に起きる

could mean, “I wake up at 8:00” such as in response to the question, “When do you wake up?” or it

could mean, “I will wake up at 8:00” such as in response to the question, “When will you wake up

tomorrow?” Furthermore, the subject of these sentences can change depending on context. For

example, the sentences above could mean, “She will wake up at 8:00” or, “They wake up at 8:00”.

Context is the only way to tell which of these numerous options they mean.

One thing I particularly struggled with in regards to this non-past idea is that things you are currently doing do not fall into this category. For instance, “I am eating” is not in the past - but it does not fall into this category. Rather, it falls into the te-form category or, more specifically, the present-continuous category.

When speaking, you would only use this form when interacting with familiar people such as family or friends. When writing, though, you’d typically use this form unless you’re writing to someone specific (like an email).

Non-past, polite

This form means the same thing as the form discussed above - except it’s more polite and can be used when talking to people you’re not familiar with. This is perhaps the most common form and the one that most places teach first.

An example of this would be changing the sentence 8時に起きる to be 8時に起きます - the later

being how you’d say, “I wake up at 8:00” to someone you’re unfamiliar with and the former being how

you’d say it to your friends / family.

Past (casual)

This form is used to indicate that the verb is completed or happened before the present moment. In English, this would be referred to as the “Simple Past” form. The idea of “completed” is the key factor here.

For instance, the sentence 映画を見た (I watched a movie) falls into this category because we

know that the watching of the movie was completed. However, the sentence, 映画を見ていた (I was

watching a movie) does not fall into this category because we don’t know if the person finished

watching the film or not (instead, it falls into the “past continuous” form).

Tofugu has a pretty good article on this here that helped me understand this a bit better.

Past, polite

As before, this inflection / form means the same thing as the casual form - you just change the

way you conjugate the verbs to be more polite for people you’re not familiar with. For instance,

食べる (to eat) becomes 食べました (I ate).

て (Te) form

The て form has a lot of uses and is the basis for a bunch of grammatical concepts. For

instance, earlier in the post we mentioned the idea of a “continuous” tense. That can be made by

modifying this て form. That being said, I’m not going to go super deep into this form or the

modifications like continuous tense - but I do want to talk about the two most common use cases for

this form: linking actions / events / states together and making commands.

In regards to linking actions - if you were to say, “I woke up and went to the bathroom” - you would

use て to connect those two things together: 起きてトイレに行った. In that sentence, て acts

like the English word “and” - but it can also act as the English word “so” such as in the sentence:

頭痛で眠れなかった (I had a headache so I couldn’t sleep). If you read that sentence, you may

have noticed that we used で instead of て which is weird cause this is the て form - but

that’s just how some items in this form are conjugated 🙃

In regards to the making a command part - if you end a sentence with て it makes the statement

a command such as 起きて (wake up). Note that this is pretty informal and, if you want to use it

with people you aren’t familiar with, you should add ください after the て.

For more information on the て form, I’d recommend reading: tofugu

or lingodeer.

Potential form

The potential form is used to show ability or possibilities - similar to “can” or “be able to” in

English. In this form the verb 読む (to read) would become 読める “can read” such as in the

sentence: 日本語が読める (I can read Japanese).

This form can also be used to express “-bility” attributes of things - such as edibility,

fixability, usability, etc. For example, the verb 食べる (to eat) would become 食べられる (is

edible) such as in the sentence: この消しゴムは食べられる (This eraser is edible).

This form can also have a polite or casual tone - but it’s not common to see this form split up

into polite / casual as the other forms are. If the verb ends in る then it’s casual - whereas if

it ends in ます then it’s formal.

The volitional form (let’s)

The last form I’m going to talk about is the volitional form - which expresses volition, proposition, or invitation - similar to “let’s” or “shall we” in English.

Volition is the cognitive process by which an individual decides on and commits to a particular course of action (Wikipedia)

Some examples would be: 動物園に行こう! (Let’s go to the zoo!) and 私がカレーを作ろうか

(Shall I make the curry?)

Like the potential form, there’s a polite and casual variant of this - although they don’t tend to

be separated out like some of the other forms. If you’re using this form casually, you’ll commonly

end in ~よう whereas if you’re using this form formally, you’ll commonly end in ~ましょう.

One interesting bit about this form is that it’s not actually shown as an inflection in Jisho. I’m not actually sure why, though. If you do know - please let me know ^.^

Concluding Thoughts

It’s a bit crazy to me that there’s so many forms and that there’s an affirmative and negative variant as well as a polite and casual variant for them. I’m sure English probably has just as many - but it’s not something I’ve ever thought about before. I’m glad I took the time to try and parse each of these forms, though, as looking at the dictionary and seeing “Potential form” really meant nothing to me prior to this. In future posts I want to dive a bit further into each one of these and really learn how to use them in both the affirmative and negative ways.

Have you ever thought about inflections like this before? If so, where at? Was it in your native language or when you were learning something else?

Thanks for reading :)